Breakout

Credit: Eric Roberts

Handouts: Graphics Reference

Worked Example: Stamp Tool

Project: Bouncing Ball

File: breakout.py

Your job in this assignment is to write the classic arcade game of Breakout, which was invented by Steve Wozniak before he founded Apple with Steve Jobs (moment of silence). It is a large assignment, but entirely manageable as long as you break the problem up into pieces.

The Breakout Game

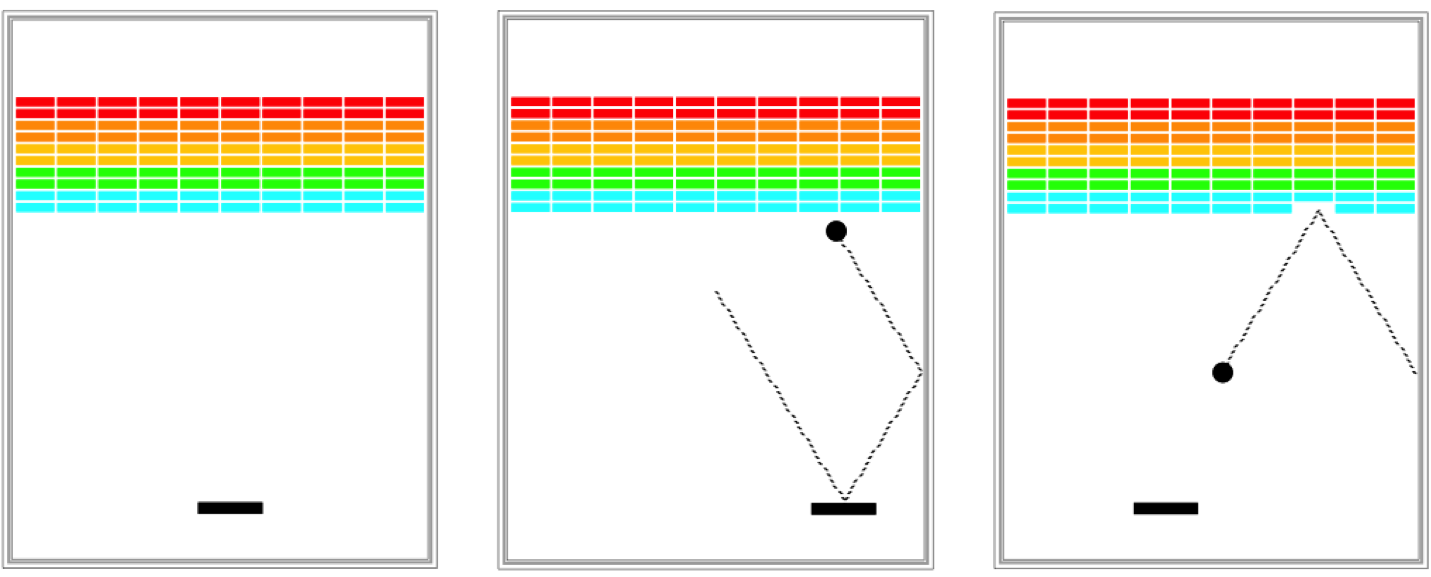

In Breakout, the initial configuration of the world appears as shown below. The colored rectangles in the top part of the screen are bricks, and the slightly larger rectangle at the bottom is the paddle. The paddle is in a fixed position in the vertical dimension, but moves back and forth across the screen along with the mouse until it reaches the edge of its space.

A complete game consists of three turns. On each turn, a ball is launched from the center of the window toward the bottom of the screen at a random angle. That ball bounces off the paddle and the walls of the world, in accordance with the physical principle generally expressed as "the angle of incidence equals the angle of reflection" (which turns out to be very easy to implement as discussed later in this handout). Thus, after two bounces--one off the paddle and one off the right wall--the ball might have the trajectory shown in the second diagram. (Note that the dotted line is there to show the ball's path and won't appear on the screen.)

As you can see from the second stage of the above diagram, the ball is about to collide with one of the bricks on the bottom row. When that happens, the ball bounces just as it does on any other collision, but the brick disappears. The third diagram shows what the game looks like after that collision and after the player has moved the paddle to put it in line with the oncoming ball.

The play on a turn continues in this way until one of two conditions occurs:

- The ball hits the lower wall, which means that the player must have missed it with the paddle. In this case, the turn ends and the next ball is served if the player has any turns left. If not, the game ends in a loss for the player.

- The last brick is eliminated. In this case, the player wins, and the game ends immediately.

Success in this assignment will depend on breaking up the problem into manageable pieces and getting each one working before you move on to the next. The next few sections describe a reasonable staged approach to the problem.

Demo

1. Create Bricks

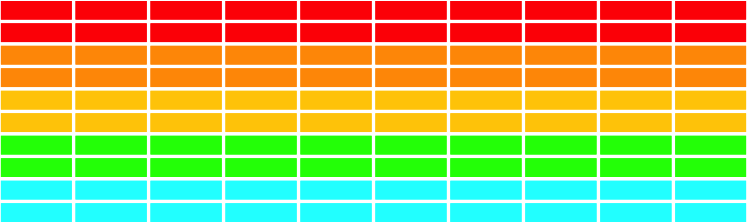

Before you start playing the game, you have to set up the various pieces. Thus, it probably makes sense to implement the main function as several smaller functions, each doing one piece of the game. An important part of the setup consists of creating the rows of bricks at the top of the game, which look like this:

The number, dimensions, and spacing of the bricks are specified using named constants in the starter file, as is the distance from the top of the window to the first line of bricks. The only value you need to compute is the x coordinate of the first column, which should be chosen so that the bricks are centered in the window, with the leftover space divided equally on the left and right sides. The color of the bricks remain constant for two rows and run in the following rainbow-like sequence: "red", "orange", "yellow", "green", "cyan".

2. Add a bouncing ball

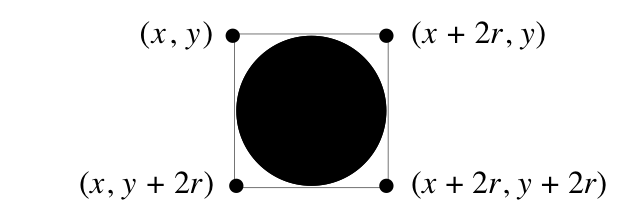

At one level, creating the ball is easy, given that it's just a filled oval. The interesting part lies in getting it to move and bounce appropriately. You are now past the "setup" phase and into the "play" phase of the game. To start, create a ball and put it in the center of the window. As you do so, keep in mind that the coordinates of the oval do not specify the location of the center of the ball but rather its upper left corner.

The program needs to keep track of the velocity of the ball, which consists of two separate components, which you will presumably declare as variables like this:

change_x = 10

change_y = 10

The "change" components represent the change in position that occurs on each time step. Initially, the ball should be heading downward, and you should pick random initial values for change_x and change_y.

Recall that there are two ways to move an object in the Python graphics library:

# Move to the object to a specific new_x, new_y

canvas.moveto(object, new_x, new_y)

# Increase the x coordinate by change_x and the y coordinate by change_y

canvas.move(object, change_x, change_y)

Once you've created your ball and the change variables, your next challenge is to get the ball to bounce around the world, ignoring entirely the paddle and the bricks. This will require that you program an "animation loop" where you move the ball, update the canvas and then pause. Then you can consider how to make the ball bounce. To do so, you need to check to see if the coordinates of the ball have gone beyond the boundary, taking into account that the ball has a nonzero size. Thus, to see if the ball has bounced off the right wall, you need to see whether the coordinate of the right edge of the ball has become greater than the width of the window; the other three directions are treated similarly. For now, have the ball bounce off the bottom wall so that you can watch it make its path around the world.

Computing what happens after a bounce is extremely simple. If a ball bounces off the top or bottom wall, all you need to do is reverse the sign of change_y. Symmetrically, bounces off the side walls simply reverse the sign of change_x. Something that might be helpful is to make a function that handles the bouncing and changing of change_x and change_y and returns the new values of change_x and change_y. You can have a function that returns more than one value:

x, y = my_func(...)

...

def my_func(...):

...

return var1, var2

3. Add the paddle

The next step is to create the paddle. There is only one paddle, which is a filled rectangle. You even know its position relative to the bottom of the window.

The challenge in creating the paddle is to make it track the mouse. Here, however, you only have to pay attention to the x coordinate of the mouse because the y position of the paddle is fixed.

Each time through the animation loop, ask for the location of the mouse and move the rectangle representing the paddle. To get the location of the mouse, you can use the canvas function canvas.get_mouse_x():

mouse_x = canvas.get_mouse_x()

4. Check for Collisions

Now comes the interesting part. In order to make Breakout into a real game, you have to be able to tell whether the ball is colliding with another object in the window. There is a canvas function: canvas.find_overlapping(x_1, y_1, x_2, y_2), which returns a list of all objects that are overlapping the rectangle with upper-left corner at (x_1, y_1) and bottom-right corner at (x_2, y_2).

colliders = canvas.find_overlapping(x_1, y_1, x_2, y_2)

The easiest thing to do, which is in fact typical of real computer games, is to check a larger bounding box for collision. Look for any objects in this rectangle:

To get a list of objects that are overlapping the ball, you can use code as follows which calls the canvas function canvas.coords(obj), returning the coordinates of the top-left and bottom-right of the object.

# this graphics function gets the location of the ball as a list

ball_coords = canvas.coords(ball)

# the list has the coordinates for two points

x_1 = ball_coords[0]

y_1 = ball_coords[1]

x_2 = ball_coords[2]

y_2 = ball_coords[3]

# we can then get a list of all objects in that area

colliding_list = canvas.find_overlapping(x_1, y_1, x_2, y_2)

If you get all overlapping objects in this rectangle, you will be returned a list. In that list will be the ball itself (since the ball overlaps too!), as well as any objects that the ball is currently colliding with. To test if a colliding object is the ball, you can simply check if the element is == to your ball variable.

If the ball collides with the paddle, you need to bounce the ball so that it starts traveling up. If it isn't the paddle, the only other thing it might be is a brick, since those are the only other objects in the world. Once again, you need to cause a bounce in the vertical direction (flip the direction of the change_y variable), but you also need to take the brick away. To do so, all you need to do is remove it from the screen by calling the delete function:

canvas.delete(square) # deletes the object called square

The ball should collide with just one object (e.g. paddle, brick) per animation cycle. In other words, as soon as you find out that the ball collided with the paddle or with a brick, you should respond to that collision and ignore the rest if it also collided e.g. with other bricks simultaneously.

5. Finishing Touches

If you've gotten to here, you've done all the hard parts. There are, however, a few more details you should take into account.

- Take care of the case when the ball hits the bottom wall. In the prototype you've been building, the ball just bounces off this wall like all the others, but that makes the game pretty hard to lose. Modify your loop structure so that it tests for hitting the bottom wall as one of its terminating conditions.

- Check for the other terminating condition, which is hitting the last brick. How do you know when you've done so? Although there are other ways to do it, one of the easiest is to have your program keep track of the number of bricks remaining. Every time you hit one, subtract one from that counter. When the count reaches zero, you must be done. It would be nice to give the player a little feedback that at least indicates whether the game was won or lost.

- Make your game play three turns!

- Test your program to see that it works. If you think everything is working, here is something to try: Just before the ball is going to pass the paddle level, move the paddle quickly so that the paddle collides with the ball rather than vice-versa. Does everything still work, or does your ball seem to get "glued" to the paddle? This error occurs because the ball collides with the paddle, changes direction, and then collides with the paddle again before escaping. How can you fix this bug?

Extensions

If you have the basic play working well, then this would be a great opportunity to go above and beyond. Here are a few ideas of for possible extensions (of course, we encourage you to use your imagination to come up with other ideas as well):

- Add sounds. It can be fun to add sound effects to your game, such as a sound whenever the ball bounces, whenever a brick is removed, whenever the user wins, and so forth. To do this, first, add the sound file you want to use to your PyCharm project on your computer. (Drag the file into the folder containing the project files on your computer). Then, you'll need to install the library that can play sound files. First open a "terminal" window: the easiest way to do this is to use the “Terminal” tab within PyCharm on the lower-left (next to the “Run” and “Python Console” tabs). Type the following 2 commands below into the Terminal. The second one is for Mac only. On Windows, type

pyinstead ofpython3:

> python3 -m pip install playsound

...prints stuff...

> python3 -m pip install pyobjc

...prints stuff...

Next, add the following import at the top of your program - make sure to use the correct one for Mac or PC:

# Use this for Mac

from playsound import playsound

# Use this for PC

from winsound import PlaySound,SND_FILENAME,SND_ASYNC

Finally, whenever you want to play a sound in your program, call the following function - make sure to use the correct one for Mac or PC:

# Use this for Mac

playsound('mysoundfile.au', block=False)

# Use this for PC

PlaySound('mysoundfile.au', SND_FILENAME | SND_ASYNC)

You should replace 'mysoundfile.au' with the name of the sound file in your project.

We include bounce.au as a bounce sound you can use. On Windows, you should use the included bounce.wav sound instead (.au files won't work).

- Improve the user control over bounces. The program gets rather boring if the only thing the player has to do is hit the ball. It is far more interesting if the player can control the ball by hitting it at different parts of the paddle. The way the old arcade game worked was that the ball would bounce in both the x and y directions if you hit it on the edge of the paddle from which the ball was coming. The web version implements this feature.

- Use your imagination. What else have you always wanted a game like this to do?